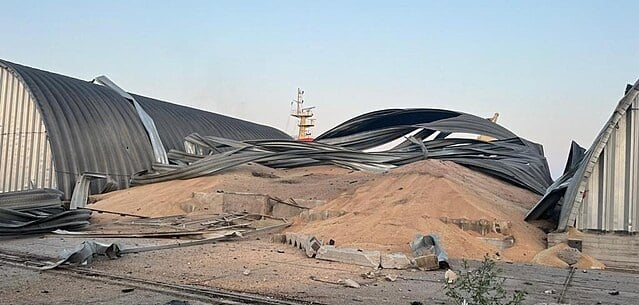

Photo: Port infrastructure in Odesa region after Russian attack – Wikimedia Commons

Since last July, the so-called “Black Sea Grain Initiative” has come to an end after a year. The term was not extended again at the hands of President Putin. The Kremlin believes that the West must comply with Russian demands around lifting sanctions if it wants to extend the deal again. While Western sanctions do not burden Russian food exports, they do burden international payments and thus the logistics of all exports. Sanction relief seems necessary for Russia to keep its head above water economically as the exchange rate of the Russian rouble sinks. Blackmail, Western countries call Russia’s demands. The (provisional) end of the Grain Deal is not only hard to swallow for Ukraine but for the grain market and food security worldwide.

Black Sea Grain Initiative

In the summer of 2022, under the watchful eye of Turkey and the UN, the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI) was signed by Russia and Ukraine. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, all Black Sea ports were also blocked, bringing grain trade to a complete halt. Millions of tonnes of grain could not be exported. Thanks to the deal, Ukraine was still able to export grain through its ports. And just about right, because Ukraine is called “the granary of the world” for good reason. The halt in trade caused huge increases in food prices, worldwide. Millions of people, especially in the Middle East and Africa, ended up in a food shortage situation. Since the deal was signed, Ukraine has exported more than 32 million tonnes of maize, grain and other cereals.

The biggest hit

The deal stabilised the global market. Global food prices fell by about 20%. Food prices are now expected to rise again if a new deal is not imminent. Even though almost half of exports were shipped to high-income countries that can somewhat afford it, the price increases will hit countries in the Global South the hardest. The implications for countries mainly in the Middle East and Africa are huge. A third of Sub-Saharan Africa’s grain imports come from Russia and Ukraine. In vulnerable countries in the Horn of Africa, for example, where food security is already a daily problem, this could lead to serious food shortages.

Meanwhile, Putin himself is negotiating with six African countries for the supply of cheap Russian grain, with the idea of getting these countries on Russia’s side. However, Russian grain exports remain below the quantities Ukraine can supply. Ultimately, Ukrainian grain is barred, leaving countries with little choice and they will opt for cheap Russian grain. Food is thus used as a weapon against the most vulnerable.

Attacks on Ukrainian ports

Meanwhile, all ships sailing on the Black Sea are seen as enemy ships of Russia and thus as ‘military targets’. In this way, Russia ensures that no ship can dock in a Ukrainian port, making it impossible to export grain without a deal. In addition, attacks on ports and grain storage sites in Odesa and cities along the Danube have been carried out since the grain deal expired. Airstrikes have destroyed thousands of tonnes of grain. The grain deal provided relative peace on the Black Sea, but since July it has thus become an operational war zone again.

Impact of sanctions on Russian economy

Moscow, through the end of the grain deal, is trying to put pressure on the West to ease economic sanctions. Russia has been disconnected from payment system SWIFT in steps during the months following the Russian invasion, and this act seems to be gradually bearing fruit. Initially, the sanctions imposed by Western countries seemed to have limited effect. The IMF even predicted that the Russian economy would grow by 0.7% in 2023. Indeed, large amounts of oil are still being exported, despite the sanctions. Meanwhile, the Russian economy is experiencing hard times – the sanctions are weighing heavily on the value of Russian currency. The Russian rouble has already depreciated by 40 per cent this year. Indeed, not being able to use SWIFT complicates Russian exports, reducing demand for the rouble, resulting in high inflation. In the medium to long term, this does not seem sustainable.

Unsuccessful negotiations

Putin, meanwhile, has been in talks with Turkish President Erdoğan, once again posing himself as a mediator and hoping to reach a new deal. This does not yet seem imminent. Putin insists and puts the ball in the West’s court. “Renewal of the deal will take place only if sanctions are eased.” As long as Russia’s invasion continues, sanctions relief for Western countries is not an option. Besides, sanctions seem to be slowly yielding results. In particular, the priority now is to close so-called ‘sanction loopholes’ through which certain exports such as oil still find their way to Europe.

The import of affordable grain is literally vital for a large number of countries and the Russian government’s cynical worldview is causing suffering in Ukraine, as well as around the world. Giving in to this political game is not an option with an unreliable partner like Russia. Pressing ahead with sanctions and continuing to support Ukraine remains the only path to peace.

Written by Timon Driessen