Photo: Mahmoud Abbas, Wikimedia Commons

On the 11th of August, Mahmoud Abbas, President of the Palestinian Authority (PA), fired twelve governors in the occupied West Bank and the Gaza Strip. For the remaining three governors, the President announced that he will also suggest replacements. Although this political reorganisation is an obvious attempt to respond to the growing frustration and disillusionment of Palestinians with the unpopular PA, Abbas’ recent move is unlikely to make a significant difference for this deep-rooted problem. This article will explain why many more reforms are required to properly address the structural issues negatively affecting the Palestinian Authority and its legitimacy.

Subordination to Israel

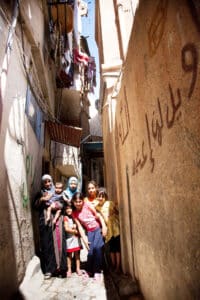

The present situation in the West Bank involves a division into 165 Palestinian enclaves. These areas operate under the partial rule of the PA. The rest, including 200 Israeli settlements, falls under complete Israeli rule. This political division was established under the 1993 Oslo Accords. However, these accords originally created the PA as an interim governing body which was meant to lead to an independent Palestinian state, including East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Gaza strip, after a five year period. This desired outcome has structurally been undermined by the illegal Israeli occupation, which makes the creation of a Palestinian state impossible.

Not only does the PA merely control a small portion of occupied Palestinian territory in the West Bank, their rule is also largely subject to approval by Israel. For instance, the authority is forced to help Israel with arrests and share intelligence with the country under the principle of ‘security coordination’. For these reasons, the Palestinian leadership is mostly seen as a ‘subcontractor’ of the Israeli occupation without any authority or legitimacy on its own.

Recently, these conditions have gotten even worse, as the current far-right, orthodox, and nationalist Israeli government has imposed several sanctions against the PA, and openly called for a complete annexation of the West Bank, which would include the collapse of the Palestinian Authority.

Lack of protection

Another negative consequence of the current Israeli Netanyahu-led government is the increase in settlements, military raids, and settler violence: according to the United Nations, 2023 has already become the deadliest year for Palestinians in the West Bank since the second Intifada. This surge in settler attacks has also triggered a re-emergence of Palestinian armed resistance. As a result, according to Al Jazeera, the Palestinian leadership is pressured by Israel to suppress these resistance fighters, instead of protecting them. This includes a “quiet process of the PA bribing fighters, particularly in Nablus, to hand themselves and their weapons over in exchange for amnesty from Israel if they serve time in PA prisons.” Under the principle of ‘divide and conquer’, this has led Paletinians and the Palestinian Authority, while both condemning the Israeli occupation, to also fight each other.

This expansion of anti-Palestinian violence thus further weakens the rule of the PA, which does not have the power to protect Palestians from Israeli violence as it does not have full control over Palestinian territory. This seriously undermines the legitimacy of the authority, which many now see as one of the obstacles in ending the illegal occupation.

Internal instability

The perceived lack of legitimacy of the PA is not only caused by its subordination to Israel and its consequential failure of protecting its citizens. It also faces significant internal challenges which cause further destabilisation. However, one might argue that the authority’s internal instability is still indirectly caused by outside influences.

One of the reasons for its internal weaknesses stems back to 2006, when the militant islamic group Hamas won the Palestinian legislative elections, which the secular Fatah party responded to by launching a preemptive coup. Violent confrontations followed and led to Hamas governing the Gaza Strip while Fatah, the dominant party of the PA, ‘controls’ the West Bank. This means that the Palestinian Authority can only exercise power over the West Bank, although it still claims the Gaza Strip, where it has installed symbolic governors, four of whom have also been fired recently.

The PA leadership is also plagued by a patriarchal culture of politicians who act out of self-interest for personal benefits: many of its key figures are elderly men who are clinging to their little share of power. The most notable example is that 87-year-old President Abbas was elected to serve as President from 2005 until 2009, but has refused to hold elections since 2006, meaning he has already been serving 14 years beyond his term. However, it is questionable whether elections under occupation can be democratic in the first place. Abbas states that the reason for the constant postponement of elections is the refusal of Israel to let Palestinians in Jerusalem participate in these elections. However, critics argue that the decision is due to the expectation that Hamas will win the elections. The move to postpone general elections has been widely denounced by Palestinians and resulted in protests, again leading the PA and Palestinians to argue against each other.

These internal divisions also concern the high uncertainty of who will succeed Abbas, in case the presidency becomes vacant. Under the Palestinian Basic Law, the speaker of the Palestinian Legislative Council would temporarily become President in such an instance. However, in 2018, Abbas dissolved the PLC and, as aforementioned, new elections have not been held.

For these deep-rooted internal and external issues, the replacement of twelve governors will unfortunately not be enough to structurally restore its legitimacy. Instead, its internal democratic culture, its power, and its relation to Israel has to be fundamentally reformed. This does not only require efforts by the PA, but mostly asks for international cooperation and justice for the whole of Palestine in the shape of the right to self-determination.

Written by Luna Sent