After a vote on the 23rd of March, all EU members decided unanimously that Albania and North Macedonia should join the European Union and three days later gave their approval to start formal talks with the countries. Both countries have attempted to join the EU for years, but disagreement among EU member states about their readiness for membership caused severe delays. It was only after the European Commission reformed the enlargement process and Albania and North Macedonia made further governmental, economic and rule-of-law changes, that unanimous approval for accession was possible. So far there is no starting date set for the talks, which are expected to take several years.

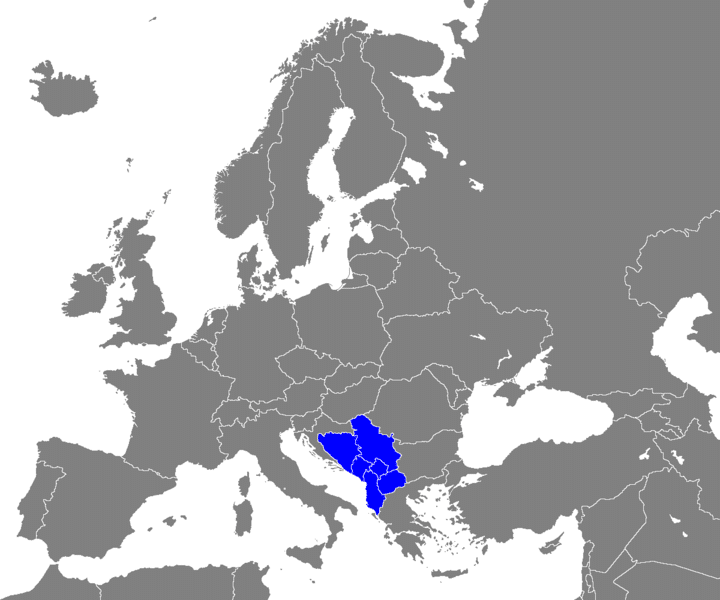

The Western Balkan

The EU membership of Albania and North Macedonia has big implications for the whole of the Western Balkans. Not only does the membership of two of the regions’ countries pave the way for other countries to follow, but the conditions the EU has set for accession will greatly influence the relationships between countries in the Western Balkans. The European Commission has made it clear that prospective member states need to have ‘good neighbourly relations’ because “the EU cannot and will not import bilateral disputes and the instability they can entail.” This means that states that want to join the union will first need to have settled their bilateral disputed.

In the Western Balkans most disputes include disagreements over borders, a remanence of former Yugoslavia where demarcations were not always precisely defined. Finding a solution will be a massive challenge for the Western Balkan countries and the EU. In most cases the dispute is an issue that is vital to the survival of a state and include national and international security concerns. However, the inclusion of Western Balkan countries in the EU’s enlargement policy has given governments the incentive to settle these dispute. The prospect of EU accession has played a major role in solving ethnic conflict and bilateral challenges in the region since 2001. One example of this is the conclusion of the long-running dispute between Greece and North Macedonia over the latter’s name. The prospect of EU accession gave the North Macedonian government the incentive to change the country’s name from Macedonia to North Macedonia and improve relations with Greece.

Not only that, but in order to qualify for EU accession countries need to make reforms regarding their governance, economics and rule of law in order to fulfil EU standards. These reforms ultimately benefit human rights in the region. For example, the EU accession process remains a driving force for change in the recognition of human rights of LGBTI people throughout the region. Human rights of LGBTI people have continuously been featured in reports, assessing the progress a potential EU candidate has made to date as well as providing recommendations for governments to implement to further improve human rights.

Even though the EU’s influence in the region has increased over time, some disputes are difficult to solve even the EU’s help. This is evident in the case of the Serbia-Kosovo dispute. Both countries aspire to join the EU – Kosovo as a potential candidate and Serbia already as a candidate country. Accession negotiations with Serbia started back in 2014 but they have not been easy. Even though both countries resolved some of the issues between them in 2011, the main disagreements regarding Kosovo’s Serb minority and the recognition of Kosovo as an independent state by Serbia remain. The EU has been a key player in the dispute for a long time. While they helped facilitate 33 agreements, dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia stalled in 2016 when Kosovo implemented 100% import tariffs on Serbian goods.

The fact that progress has stalled indicates that domestic political pressures outweigh the still distant prospect of EU accession. In 2018 only 29% percent of Serbians declared that they were in favour of EU membership which is substantially less than in other Western Balkan countries. At the same time, 80% of Serbians declared that they were against the recognition of Kosovo, even in exchange for faster EU accession. These numbers could indicate that in recent times at least, the influence of the EU in the region is waning.

What has especially weakened the EU’s influence in the region is the EU’s lacking commitment to further enlargement. Particularly France’s veto in October 2019 to start accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia has created doubt among Western Balkan countries regarding their future as an EU member state. France’s call to reform the EU’s enlargement policy meant that integration slowed down, decreasing public expectation in the region to join the EU in the near future even more (which is evident from the Serbian numbers). This perceived lack of commitment by the EU will most likely also have an affect on resolving bilateral problems because the incentive for governments to do so is increasingly becoming less. The incentive to make further reforms, or uphold already made reforms, in other fields will most likely also decrease. This is already evident when it comes to compliance with EU human rights standards, especially LGBTI human rights. The progress that was made regarding LGBTI rights in the region is still fragile and therefore support from European institutions is key. LGBTI organisations and activists in the Western Balkans have already expressed great concerns about the development of LGBTI human rights since France’s veto in October 2019. Hopefully, now that Albania and North Macedonia have started talks with the EU the will to develop (LGBTI) human rights will increase again.

Furthermore, another effect of the lack of EU commitment could be that since a future in the EU is perceived to be less likely, the countries will look for partnerships elsewhere (for example with Russia or China). Russia and the EU in particular have been competing over influence in the Western Balkan for years. However, the seriousness of the ‘Russian threat’ in the Western Balkan has divided EU member states. Whilst some countries such as France and the Netherlands pressed for reforms first and a slower approach overall, other countries were eager to move quickly. Their approach is clearly fuelled by not only having to counter Russia’s increasing influence in the region, but also China’s influence.

Russia

Since the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s the region has been a point of debate when it comes to EU/NATO enlargement, EU security and defence and transatlantic relations. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia has attempted to re-establish itself as a world player, but it has especially attempted to become a major player in Europe’s security affairs just like countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom and France. The geographical location of the Western Balkans places them firmly between the EU and Russia. Subsequently, whoever manages to have the most influence in the region will have a strong strategic position to influence both EU security matters as well as Russian ones. The European Union is trying to get a hold of the Western Balkans in an attempt to keep Russia at bay and Russia is doing the same for the EU and NATO. Thus from a geopolitical point of view the region is extremely important security wise.

Historically, the Western Balkan region lies well beyond Russia’s considered “sphere of influence” in Eastern Europe. In economic, geographic and social terms, the region has always gravitated more towards the West than towards Russia. Therefore, Russia’s only option has been to undermine the EU (as well as NATO) by using the region’s own vulnerabilities against them. Russia thus does not necessarily want to bring the region into its own orbit, but instead wants influence over it to have leverage against the EU. From Russia’s perspective, if the EU can meddle in Russia’s ‘backyard’ (e.g. Ukraine, Georgia etc.), then Russia can do the same to the EU.

So what tools does Russia use to accomplish this? In the case of the Western Balkans it has attempted to use old nationalist fuelled disputes, citizen’s distrust in public institutions, pervasive corruption and state capture as ways to stop the Western Balkan countries to join the EU as well as NATO. More generally, Russia mostly uses coercion, co-optation and subversion to attain their goals.

Russia applies military coercion to the Western Balkans to a lesser extent than its soft coercion and subversion. Even though Russia does use military power to attain its goals, it more so manipulates economic ties, sets up targeted campaigns to influence public opinion, uses cyberattacks, impose trade embargos and interferes in the internal affairs of other countries. One example of their interference is that in some of the cases of pro-EU and NATO countries, such as North Macedonia, Russia has given support to nationalist activists in an attempt to disrupt the peace and start an internal crisis.

Co-optation however is the strategy Russia uses most often in the Western Balkans. This can most clearly be seen in Serbia. Russia has built alliances with local power holders in Serbia as well as Bosnia-Herzegovina’s ‘Republika Srpska’. Incentives to build partnerships with Russia vary from monetary gain to influencing the balance of power at the regional or domestic level. In Serbia’s case, working with Russia has not only maximised its leverage over the Kosovo issue, but also strengthen investment and business ties (which no doubt includes side payments for some actors). For Republica Srpska increasing ties with Russia means that they can resist pressures from the West more easily as well as from major Bosniak parties who favour greater centralisation of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

However, in recent years, a new player arrived in the Western Balkan that can decrease the EU’s influence even more. China is now also attempting to increase its influence, and thus its strategic position in Europe, in the Western Balkans. In recent years a massive increase of Chinese investments, such as infrastructure and telecommunication projects, can be witnessed. These projects is something that Russia cannot offer the region, giving China the possibility to increase their influence in the region steadily.

China

China interest in the region is not so much political, but more geo-economical. By increasing its influence, China is attempting to use the Western Balkans as a gateway and transit commercial platform to Western Europe which is the region they are really interested in. Despite the regions proximity to the EU, it is debt burdened and cash strapped. Unemployment rates are at average 20% and the economy is in desperate need for investment. China has taken this chance by investing money into the region to quickly gain influence. They have taken advantage of the poor investment climate by providing loans and consequently ensuring long term dependency. Regardless, China faces little resistance from the region.

China is capital rich and ready to outspend many Western actors in the region. Chinese companies are mainly state owned, which brings with it large government subsidies. Not only that, but China is willing to build at low costs, by not meeting environmental and social standards. The large infrastructure deficits of the region together with the lack of capital, lax public procurement rules, poor labour regulations and loose regulation practices is very appealing to Chinese investors who are looking to establish bases and invest in the EU’s backyard quickly.

Back in 2013 China announced that it would invest $900 billion dollars in a project that was to connect international trade routes in a modern-day Silk Road (now known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)). Even though increased investment in the Western Balkans is arguably good for the development of the whole region, the BRI project hinders the Western Balkan’s integration into the EU in three ways: trapping countries into debt, lowering environmental standards and preserving corruption.

As mentioned above, the so called debt trap diplomacy entails that China loans countries money that have no realistic way of paying it back. These countries become economically dependent on China and in turn makes them vulnerable to Chinese political influence as well. One example of this is China’s highway project in Montenegro. Montenegro wanted to build a highway between its port city of Bar and Serbia’s capital Belgrade. China agreed to build the highway despite several studies indicating that Montenegro has no way of paying China back. Regardless of what China’s intentions were, the EU will be hesitant to adopt a new member state that is not only in the position to be exploited by China on a variety of issues, but also has an ever worsening debt situation.

Moreover, as part of the EU integration process, the Western Balkan countries have joined the Energy Community Treaty (ECT). This treaty makes sure that the regions environmental policies and pollution standards are in line with those of the EU. Most relevant to the region, this treaty has a component in which countries have to start weaning themselves of fossil fuels. However, several Western Balkan countries, for example Bosnia-Herzegovina, have contracted Chinese companies to build them coal power units. The EU has taken this as a message that Bosnia-Herzegovina (and other countries) do not take their commitment to EU rules and international treaties seriously. The BRI undermines the EU by offering an alternative to political leaders who value short-term political gain over their country’s long-term prosperity.

Not only that, but inherent to the BRI is the spread and exploitation of corrupt political networks in local governments. One of the main ways that China maintains corruption in the region is by not holding transparent bidding processes for BRI contracts. A clear example of this can be found in North Macedonia. It came to light that former prime minister Gruevski and transportation minister Janakieski were going to award a contract to build two highways to the Chinese company ‘Sinohydro’ because they were willing to pay a bribe of around €25 million. Corruption is one of the biggest obstacles the Western Balkans face when it comes to EU accession. In a report from the European Parliament it states that corruption “is a phenomenon that poses a threat to the EU’s core values, such as democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights, and undermines good governance and economic development. For these reasons, anti-corruption reform is among the key requirements for EU accession.”

Conclusion

As mentioned above, the lacking (or at least perceived lacking) of the EU commitment to the Western Balkans has only reinforced the region’s sense of abandonment. This has made them more susceptible to not only the disruptive tactics of Russia, but has also increasingly motivated them to look for partnerships elsewhere. The EU should increase its commitment to the region and speed up its enlargement process if it does not want to decrease its influence even further. Similarly, both NATO and the EU should focus on Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina because they are the countries right now that are leaning more towards partnership with Russia than the EU. It is very important for the region’s stability that the whole of the Western Balkans see a similar future for their respective countries, hopefully in the EU.

It is also important to not underestimate the relatively new influence of China in the region. The increased presence of China in the region is a direct result of a power vacuum that was created by the EU itself. The EU’s lack of commitment to the region has made it possible for China to transform the Western Balkans from a relative non-actor to one of its most important foreign actors in a very short time. If the EU does not increase its commitment to the region fast, it will give either China or Russia the possibility to shape the region’s future. Hopefully the accession of Albania and North Macedonia to the EU will have send a clear message to the people of the Western Balkans of the EU’s re-commitment to the region. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel recently states, “there will only be a truly united Europe with the states of the Western Balkans.”

Sources: Republic Word / Radio Free Europe / The Guardian / The Globe Post / Atlantic Council / European Council on Foreign Relations / The Parliament Magazine / European Parliament 1 / European Parliament 2 / FRAME / Emerging Europe / The Diplomat 1 / The Diplomat 2

Photo: Wikimedia