Soldiers of a PMF-militia in Tal Afar | Photo: Mohammed Mehdi Dara | Source: Wikimedia C0mmons

On 10 March 2023, even experts were surprised by an equally monumental and seemingly impossible development in the Middle East: Iran and Saudi Arabia had restored their diplomatic ties after mediation by China. In the blink of an eye, two of the Middle East’s important super powers had taken an important step towards ending their long-standing rivalry. In recent years, the ‘Saudi-Iranian cold war’ – as some have called it – has played an important role in a great variety of armed conflicts in the Middle East, most prominently through the use of proxy forces in countries like Yemen, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq. The Saudi-Iranian détente, therefore, provides great potential for the abatement of violence throughout the region.

To visualize this potential ‘on the ground’, it is interesting to zoom in on a specific area where the ambition of Tehran and Riyadh currently leads to friction. This article will explore the possibilities of the rapprochement between Saudi-Arabia and Iran by looking at the case of Iraq. The country makes for an interesting case to explore in depth, all the more for its mediating role in the rapprochement. Before we can make a prediction of the possible consequences for Iraq, it is important to determine the state of affairs regarding the Saudi-Iranian deal, current political situation in Iraq and the influence that both Iran and Saudi Arabia have in the country.

Saudi-Iranian détente: what we know so far

While the agreement may have shocked the world of international relations, internal crises and ambitions in both Iran and Saudi Arabia can explain this development to a great extent. For Tehran, the rapprochement was urgently needed from an economic point of view. Sanctions imposed by the United States and European Union have ravaged its economy and were one of the main reasons behind the uprising following the death of Mahsa Amini. Restoring ties with Saudi Arabia and its allies in the Arab Gulf could pave the way for foreign investments and economic growth.

For Riyadh – on the other hand – improving regional stability is vital to its future ambitions. The effectively ruling Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman – through his plan Vision 2030 – has been attempting to reduce Saudi dependence on oil and “create a knowledge and service-based economy.” To this end, Bin Salman desperately needs foreign investments that are – besides the appalling human rights record – currently obstructed by turmoil close to home, such as the conflict in Yemen.

The question remains, however, if Riyadh and Tehran can simply set aside over four decades of rivalry. Possible breaking points looming over the agreement include the matter of Israel. Saudi Arabia has a history of secretive cooperation with Israel and has allowed Jerusalem to forge bonds with some of its allies through the Abraham Accords (2020). Iran, on the contrary, remains one of Israel’s arch enemies. Further Israeli-Iranian hostility could put the Saudi-Iranian relationship under early pressure. Another threat is the possible return of a Republican to the White House in 2024. Most Republicans aim for an aggressive anti-Iranian policy and will likely pressure Riyadh to join Washington in this position.

For now, nonetheless, the attempt to restore ties seems genuine based on a variety of gestures: Tehran’s embassy in Riyadh has reopened, commercial flights between the two countries will reportedly be reestablished and Iranian President Ibrahim Raisi is expected to visit Saudi Arabia soon. Ayham Kamel – head of Middle East research at the Eurasia Group – predicts a gradual progress in relations: “You don’t shift from competition to significant cooperation overnight. I suspect Iran-Gulf relations are going to be taken out of an era of confrontation to a more natural one where there are disagreements, competition and cooperation.”

A new government and looming crises: the Iraqi political context

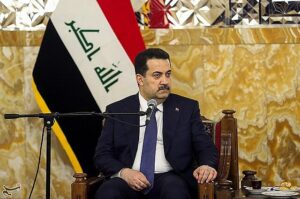

In Iraq – after a long period of political unrest – a relative stability has returned since the new government under Prime Minister Mohammed Shiya al-Sudani assumed office in October 2022. Before al-Sudani rose to power, Iraq had been in a political gridlock for over a year. In October 2021, powerful Shia leader and cleric Muqtada al-Sadr and his Sadrist movement – which is Shia but considered against Iranian influence in Iraq – won the parliamentary election by obtaining 73 seats. Since Iraqi parliament has a total of 329 seats, however, al-Sadr was forced to seek collaboration with other movements. This is where al-Sadr failed: he was unable to make a deal with the Coordination Framework Alliance (CFA) – a rival Shia movement which is supported by Iran – and gradually lost the momentum. After violent clashes between supporters of both Shia movements, al-Sudani and politician Abdul Latif Rashid took over the initiative and were named Prime Minister and President respectively.

Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani | Photo: Nima Najazadeh| Source: Wikimedia Commons

Since his rise to power, al-Sudani has – according to researchers of the Dutch Clingendael Institute – “given a crash course on how to please all sides”. Furthermore, al-Sudani seems to know how to balance his policy between the needs of Iraq’s powerful elite political factions. The same can be said of al-Sudani’s foreign policy: he has met regularly with both the US ambassador and Iranian government officials, has visited France and Germany, and has refrained from polarizing rhetoric during those visits.

On a more critical note, Clingendael’s researchers point out that al-Sudani has equally refrained from introducing overdue reforms that are vital to Iraq’s economy, education, healthcare and governance. “Although Iraq’s immediate future is secured by its oil wealth, it is economically vulnerable in the long term.” This criticism is echoed by Omar al-Nidawi, analyst at the Enabling Peace in Iraq Center. Al-Nidawi added that militias supported by Tehran have further expanded their power in Iraq and fears that al-Sudani is “a mere general manager who serves at the pleasure of the CFA’s leaders, enabling them to operate under continued impunity. Al-Sudani has consistently put the interests of his benefactors ahead of those of the public.”

In short, while al-Sudani has given Iraq much-needed stability after a relatively chaotic period, there exist doubts surrounding whether he is the right man to guide the country past its more long-term challenges.

The comprehensive Iranian network of influence in Iraq

Historically speaking, Iran and Iraq have a multifaceted and complex relationship. “You simply cannot move Iraq and Iran apart,” according to former Iraqi President Barham Salih. Two main interests are generally identified for Tehran’s involvement in Iraq: preventing renewed hostility from Baghdad after the bloody 1980-1988 war and removing US influence from Iraq. In the last four decades, Iran-Iraq relations have shifted from a destructive military conflict into a comprehensive Iranian presence in Iraq, especially since the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the death of Saddam Hussein in 2006.

The two countries’ interconnectedness comes forward in the field of religion. In both Iran – around 90% – and Iraq – around 60% – Shia Muslims form the majority of the population. “The religious conservative part of Shia Iraq has always been susceptible to Iranian influence, though not all Shia are pro-Iran,” Andreas Krieg, an associate professor at the Defence Studies Department of King’s College London, told reporters of Al Jazeera.

There is also a strong economic connection between the two countries, however. Some have even called Iraq a “cash cow” for Iran. Since the two countries share a 1599 kilometer-border, there naturally is a significant trade relation including goods from agricultural to industrial products. The economic dependence of Baghdad to Tehran is perhaps most striking in the field of energy. Historically, Iraq imports around 40% of its energy needs from Iran, although Baghdad has recently sought to reduce its dependence on Iranian energy. Other economic connections include cooperation for infrastructure projects, financial support in the form of grants and loans, and the presence of Iranian banks in Iraq.

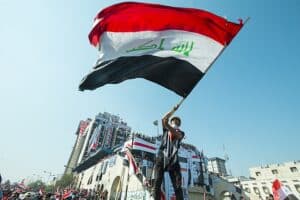

In the political area, more than a dozen Shia political parties have ties with Tehran. Most of these parties work together in the Coordination Framework, which supports Prime Minister al-Sudani. The Coordination Framework partially derives its power from a group of militias called Hashd al-Sha’bi or Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF). However, it is important to understand that the PMF is not a homogenous group or a figurehead of the Iranian regime, but an umbrella term for around 40 paramilitary units which each have differing relations with Iran, Iraqi political actors and each other. The PMF, furthermore, enjoys a broad and genuine popularity in Iraqi society, mainly deriving from its successful contribution to the fight against Islamic State. The fight that Hashd militias delivered against the terrorist Sunni group is commonly regarded as “a selfless sacrifice” in a narrative that “differs little from similar mythologies of nationalism that emerged out of war such as Russia’s Great Patriotic War or Iran’s Sacred Defense”.

It is important to note, however, that a shift in the PMF’s popularity is visible in recent months. Ranj Alaaldin, a foreign policy analyst at Brookings Institute, claims that “70% of Iraqis had a favorable view towards Iran and the PMF, particularly the Shia community. Today, that’s at 50%. And the reason for that is because the militia [the PMF] has turned their guns on Iraqis”. With this statement, Alaaldin points at attacks by PMF-aligned factions on civilian activists, including ethnic Shias. Alaaldin argues that this is part of a greater problem that the PMF faces, namely that the common enemy for Iraqi Shias – Islamic State, which many Shias saw as an “existential threat” – has virtually disappeared.

This decrease in PMF popularity is accompanied by preexisting anti-Iranian sentiment in Iraqi society. This is signified by Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, a main Shia moral and religious authority which is revered by a great number of Iraqi Shias. While al-Sistani has adopted a quietist approach regarding politics, many observers see his lack of support for Tehran as “a tacit rebuke of the Islamic Republic”. Another factor that can never be ruled out is Muqtada al-Sadr. Although al-Sadr has lost some of his political clout for now, he remains a staunch adversary of Tehran’s ‘long arm’. The Sadrist movement, moreover, remains an important political player. Experts predict that al-Sadr’s absence from politics will not last long and that violence is to be expected if Prime Minister al-Sudani ignores the interests of his supporters.

Muqtada al-Sadr (r) with Iranian leader Ali Khamenei | Source: Wikimedia Commons

On balance, while Iranian influence in Iraq is experiencing turbulence at the moment, it should still be seen as “a reality that is engrained in the country, in the fabric of the society, within the state itself”.

New momentum: Saudi Arabia’s influence in Iraq

Despite having a long history of interaction, Iraqi-Saudi relations have been relatively non-existent from Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 until the reopening of the Saudi embassy in Bagdad in 2015. While Riyadh’s break of ties with Baghdad during this period can be considered justified because of Saddam’s aggressive foreign policy, it did only decide to restore ties in 2015, 12 years after Hussein was removed from power.

Although an explanation for Riyadh’s post-2003 disinterest in Iraq is often sought in the religious area – Saudi Arabia is a main Sunni Muslim power and Iraq has a predominantly Shia Muslim population – it is a mistake to do so. According to Ken Pollack – a former Middle East intelligence specialist for the CIA – the division between Sunni and Shia Muslims undoubtedly leads to conflict in the Middle East, but “Americans, Westerns, we have have greatly exaggerated the impact of its importance”.

Katherine Harvey – Adjunct Professor at the Center for Security Studies – argues in accordance with Pollack that the Saudi-Iraqi division was not a foregone conclusion. Instead, the division was a “self-fulfilling prophecy”, created by the misguided Saudi fear that Baghdad was already aligned with Iran. Another reason for the difficult relations was the personal rivalry between the former Saudi King Abdullah and former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki.

However, since the death of Abdullah and al-Maliki’s fall from power, a lot has changed. Harvey: “Since the passing of Nouri al-Maliki and Abdullah in more recent years, there has been really an important shift in the relationship. And there’s new momentum.” According to Harvey, Saudi Arabia now sees the potential of Iraq instead of a pre-set ally of Iran.

This new Saudi-Iraqi coordination was first signified by the reopening of the Saudi embassy in Baghdad in 2015. Since then, cooperation between the two countries has tentatively increased in a number of areas. A good example is electricity: as per 2022, Iraq has been connected to the Saudi electrical grid. In February, moreover, a memorandum was signed to increase security cooperation.

Consequences of de-escalation for Iraq

If you compare Iran’s existing power base to Saudi Arabia’s more upcoming influence in Iraq, the current phase of détente could mean an opportunity for Riyadh to further expand its influence, as Iran-aligned political factions in Iraq may be less prone to obstruct Saudi involvement.

The agreement also has potential for an abatement of violence between Shia and Sunni tribes. “With Saudi and Iran not escalating, there’s hope that the sectarianism in both countries, toward the sect minorities there, will decrease, impacting positively the sectarian tensions in Iraq,” Iraqi analyst and deputy Middle East editor for New Lines magazine, Rasha al-Aqeedi, told CBS News reporters.

The potential of the deal for Iraq is reiterated by foreign relations experts. Although a common view is that the Saudi-Iranian division did not create conflicts in the Middle East on its own, it did in many cases make them more complex and violent. A removal of regional tensions from a conflict is likely to have a de-escalating effect in the long term.

The influence of the rapprochement on local tensions should, nonetheless, not be overestimated. According to Joseph Bahout – director of the Issam Fares Institute at the American University of Beirut – the restoring of ties “does not mean an end to competition, tension, or even friction between KSA [Kingdom of Saudi Arabia] and Iran, but it aims at regulating it”. While a decrease in Saudi-Iranian rivalry will undoubtedly mean less external stimulus for sectarian violence, the internal divisions in Iraq are still in place. Moreover, if support from Tehran for PMF-militias is going to be at a lower level, this will not automatically make these militias dissolve nor will their interests have disappeared. A good example illustrating this is Yemen: while Iran-backed forces will have less military clout

Besides this, many Iraqis remain skeptical towards Tehran’s promise to make changes to its large-scale involvement in Iraq. Increased investments from Saudi Arabia in Iraq, furthermore, are expected to be mainly beneficial towards the Iraqi elite. This might flare up the existing tensions in Iraqi society instead of cooling them down. In recent years, Iraq’s falling middle class has become increasingly discontent, while populist ideology is reportedly on the rise.

However, it is not exclusively skepticism that prevails. According to Al-Aqeedi, another benefit of the Saudi-Iranian reconciliation for Iraq, albeit a symbolic one, “is the return of Iraq to the center of geopolitics – not as a headache, but rather a problem-solver. It gives Iraq great leverage on the regional and international stages.”

Author: David Groenen