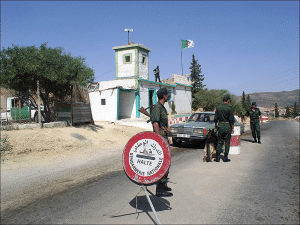

Algerian protest in 2011: Flickr

On February 23, Algerian authorities dissolved a decades-old pro-democracy group that participated in the peaceful protest which helped force the North African country’s long-time President Abdelaziz Bouteflika from office in 2019. The Youth Action Group, know as RAJ, and the left-leaning Movement for Democracy and Socialism party that was also suspended by the same degree, appear to be the latest targets of a crackdown on Algeria’s dissenting voices. Algeria has in recent months stepped up a crackdown on dissent, right groups say, after having quashed the “Hirak” mass protest movement that mobilised hundreds of thousands of demonstrators in weekly protest from 2019 and 2020.

The Algerian Council of State said RAJ was dissolved in line with an October 2021 court decision in favour of an interior ministry lawsuit. The ministry had alleged that the group is “rallying forces to destabilize the country” and conducting other activities that violate a controversial 2012 law on nongovernmental groups. RAJ leaders have repeatedly denied the government’s allegations. They stated that the authorities under President Abdel Madjid Tebbouna have rolled back on promises to reform the power structure that under former president Bouteflika was marked by corruption and repression.Iternational human rights organisations have urged Tebboune to scrap the 2012 law adopted by the Bouteflika regime that governs NGO activities.

Restrictive laws on opposition

The Law on Associations of 2012 is heavily restrictive and does not conform with international standards on freedom of association. Article 2 states the objectives of an association “must fit within the general interest and not be contrary to the national foundations and values or the public order and good morals”. Such provisions are too vaguely worded to allow association to predict whether any of its activities are a crime and threatens the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression and association, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch said. Associations should be free to determine their statutes and activities and make decisions without government interference and should not face dissolution for their legal and peaceful activities. Civil society organizations should be free to communicate with foreign non-governmental organizations, intergovernmental organizations, and international human rights bodies. “Algeria is rapidly plunging ever deeper into a human rights crisis where there is virtually no more space for human rights work and activities,” said Amna Guellali, Amnesty International’s deputy director for the Middle East and North Africa. “The authorities’ dismantling of the oldest human rights group in the country will go down in history as a shameful act that must be reversed immediately.”

Upcoming elections

The United Nations condemned the closure of the country’s largest human rights organisations. This comes amid growing repression of opposition figures associated with the liberal Hirak movement. UN Special Rapporteur Mary Lawlor accused the Algerian government of “acts of intimidation, silencing, and repression”. She continued by saying “the decision to dissolve such respected human rights associations demonstrates an alarming crackdown on civil society organizations and seriously undermined the space for human right defenders to carry out their legitimate human rights activities, and to freely associate and express themselves. The decision to dissolve those two renowned human rights organisations must be reserved”. The Algerian government is cracking down on opposition campaigners, as President Abdelmadjid Tebbouna is speculated to be preparing to seek another term in elections next year. In 2019, human rights groups helped force then-president Abdelaziz Bouteflika out of office following a wave of strikes and protests. Fearing similar treatment, Tebboune seems to be taking proactive measures.

Crushing of critical voices

Protests erupted in 2019 when seriously ill former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika appeared to be running for a third term after 20 years in power. The protest movement succeeded in thwarting Bouteflika and he was eventually forced to resign. But when the movement opposed plans later that year to hold presidential elections without first putting reforms in place, the authorities began to arrest the perceived leaders of the informal movement. The crackdown intensified after the election of Abdelmadjid Tebboune as president in December 2019, though the mass marches halted in March 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Around the second anniversary of Hirak, in February 2021, the protests resumed, but lost momentum three months later, due to repression and a weakening of the movement. Three years after the start of large-scale weekly peaceful protests for political change, authorities have detained 280 activists, who are facing or convicted on the basis of vague charges. Eric Goldstein, acting Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch said “piling on dubious charges of ‘terrorism’ and vague charges like ‘harming national unity’ cannot hide the fact that this is about crushing the critical voices of a peaceful reform movement”.

Author: Manouk Bronzwaer