On March 18th Vladimir Putin was re-elected as Russia’s President. According to official results, he received some 77% of the votes, while Pavel Grudinin of the Communist Party and Vladimir Zhirinovsky of the Liberal Democratic Party trailed by 12% and 5% respectively. The rest of the opposition candidates hovered around 1%. The Kremlin was initially aiming for a so-called 70/70 win, with Putin gaining 70% of the votes with a 70% voter turnout, to provide him with a broad mandate. Preliminary results show a 67% voter turnout. Putin’s popularity is considered quite widespread at home: the media – especially official state TV – is tightly controlled and pro-Kremlin, the opposition is largely invisible for the majority of Russians in-between elections, and was mainly depicted as a squabbling band during the campaign. Meanwhile, official polls have been only favourable for Putin, building an aura of invincibility, while the last major independent pollster announced in January it would not be publishing any poll results until the elections, out of fear of negative consequences for its operations. With Putin’s fourth – and, by law, final – term secured, the question is: What’s next?

Legitimization ritual

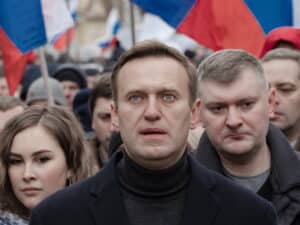

Nobody doubted that Putin would be re-elected. Many Kremlin watchers, independent experts and opposition figures called it a legitimization ritual. Instead, the main issue in this campaign was the turnout. Opposition leader Alexey Navalny, who could have been an actual challenger to Putin, after being barred from the vote turned his impressive campaign machine into a boycott one, to delegitimise the election. In response, the Kremlin tried to get as many people to the polls as possible to show Russia and the world that Putin’s mandate is legitimate. A major get-out-the-vote campaign was set up, with Kremlin-sponsored videos and posters urging voters to go to the polls. There were reports from all over the country of civil servants and students being strongly pressured to vote under threat of negative consequences.

In most voting districts Putin received at least 64% of the votes. Nonetheless the Kremlin did not get the voter turnout it hoped for: the projected 70% wasn’t reached. Especially in Moscow and St. Petersburg, traditionally hubs of opposition activity, the turnout was low with around 55%. Most of the people who went to the polls were according to an exit poll above 45 years. Only 9% of the eligible voters between 18 and 25 showed up, possibly signalling the younger generation’s fatigue with the existing system. Instances of fraud have been reported. Independent election monitor Golos said it had received reports of 2,742 alleged violations, including ballot boxes placed out of sight of observation cameras and observers being blocked from carrying out their job. Several bizarre videos were published on social media, with blatant ballot box stuffing and other violations sometimes even filmed by the official cameras of the Central Election Commission. International observers said the election was “overly controlled” and “lacked genuine competition.”

Political reactions

With the results known, the prospect of six more years of Putin evoked many reactions. Alexei Navalny’s movement, often credited as Russia’s real (and in any case most visible and vibrant) opposition, reacted with constraint. A spokesman said they would focus on the long term game, but would closely follow fraud cases, not excluding the possibility of protests similar to 2011. Navalny in a video message called on supporters not to despair, saying nothing unexpected happened and the fight would continue, commending those who heeded his boycott call. Runner-up Pavel Grudinin called it the most filthy election in recent history, saying the Kremlin undermined his campaign and that of other candidates.

In international reactions, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said it was not a “fair political competition,” according to European values and that Russia would “remain a difficult partner.” Leader of the largest fraction in the European Parliament , Manfred Weber (European People’s Party), put it more bluntly by stating that Putin’s way was “threatening our way of life”.

2024 and beyond

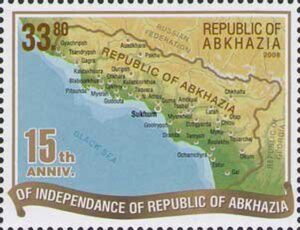

Putin himself was largely absent from the campaign. Nevertheless, even without credible opinion polls it is safe to say that many Russians genuinely support him. That support leans heavily on two main pillars. There is the positive image of the president – as hero and saviour of the Russian nation – and all he is said to have achieved, broadcast through every available media on a daily basis. Even the date of the election was chosen to be a firm reminder of Putin’s success, coinciding with the 4th anniversary of the annexation of Crimea. This image runs parallel with a perceived lack of an alternative to Putin. And there is the antagonistic stance with the West and an image of a besieged Russia surrounded by enemies, convincing many Russians that a strong president is needed. A similar tactic might well continue to be used in the coming years.

Constitutionally, Putin isn’t eligible to seek another term in 2024. The next six years will thus be crucial for him to retain a firm grip on the country. In off-hand comments to a journalist some days ago, Putin joked that he couldn’t exactly remain until he was a hundred years old. At the same time, no-one seriously entertains the idea that Vladimir Putin might one day simply decide to relinquish his power. Several possibilities remain.

One obvious possibility is a switch similar to 2008, when Putin simply switched places with his Prime Minister and loyal friend Dmitry Medvedev for one term, before returning to the Presidency: the Constitutional constraint speaks only of a limit of two consecutive terms. However, last time even such a symbolic switch gave rise to increased opposition activity, culminating in the mass protests between December 2011 and May/June 2012. The question is if Putin is willing to risk that again, at age 77 (for a re-election in 2030).

The recent Chinese example of lifting the presidential term limit could potentially present another possibility. With the legislature and judiciary as tightly controlled this does not seem difficult. In 2008 the presidential term was already prolonged from 4 to 6 years without much ado. It is difficult to predict if and what reaction a revoking of term limits would cause in society. With many Russians not seeing an alternative to Putin, except for perceived chaos, many would likely not even object. The question would be whether the opposition would still be able to mobile those that would.

There are also always rumours of a successor being prepared in the wings. However, so far, each such rumoured successor has eventually been quietly pushed out. Here the question would be if Putin is capable of finding someone he either trusts completely – to protect him and his assets unequivocally once he gives up his presidential seat – or someone he can control completely, even from the shadows, so as to remain the one in charge.

Whichever option is in fact considered in the Kremlin, it is clear in any case that there are several realistic avenues open to Putin. It will, in fact, be much more difficult for his opponents to stop the changes enabling him to remain in power, than for him to push them through. The next six years will show whether the critical part of the Russian society still has the vigor and resilience necessary in the fight to come.

Sources: rferl I rferl II BBC New York Times DW