A demonstrator stands near a burning fire blocking a road during a protest against mounting economic hardships.

Lebanon has seen the value of its currency plunge to a historic low, posing a big threat to the stability in the country. More than half the population is now in poverty, and with no government plan in sight, protests are being held throughout the country.

Protests continue to escalate

Throughout the past week, protesters all over the small country in the Middle East have blocked roads with burning tyres. The main roads leading into the capital Beirut were blocked, and in Beirut itself, protesters briefly blocked the road to the central bank. Some have called for a revival of the street movement of 2019, which demanded the removal of Lebanon’s entire political class, widely seen as incompetent and corrupt.

The protests have led to some casualties. In Tyre, a man tried to pour petrol on his body and set himself on fire, but security forces have stopped him on time,. Three men were killed in a car accident, when they drove into a lorry that was blocking a main motorway in the north of the country.

The traffic jams have prompted hospitals to sound the alarm bell. Suppliers faced difficulties in delivering supplies necessary to treat Covid-19 patients, such as oxygen.

Historic low in financial crisis

Protesters are demanding political action to end the economic crisis that has prevailed for more than a year. The protests erupted after the collapse of the Lebanese pound, which sank to a historic low last week, at 10,000 pounds to the US dollar. The currency has decreased about 85 percent in value. This was the last straw for the Lebanese.

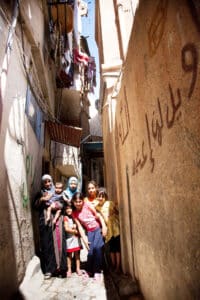

The financial crisis erupted in 2019 and has wiped out jobs, locked people out of their bank deposits and raised the risk of widespread hunger. Nearly half of the population of six million has been driven into poverty and purchasing power has plummeted. According to news reports, people in the country can barely afford basic goods such as sandwiches, or a bus journey. Bus fares have risen by 33 percent according to the Transport Ministry, and so has the price of shared taxis.

Videos have gone viral on Lebanese social media, showing customers fighting over basic products such as baby milk in supermarkets. Lebanon’s economic crisis has been aggravated by several lockdowns to stem the spread of the coronavirus pandemic.

The escalating crisis is posing a big threat to the stability in the country since the 15-year civil war, which came to an end in 1990.

Unrest in the security forces’ ranks

The Lebanese army has been clearing the roadblocks, made of burning tyres, debris, dumpsters and vehicles, as protesters obstruct roads across the country. There was a short delay in clearing the roads due to a political disagreement between the chief of the armed forces and President Aoun.

Lebanon’s president told the army and security forces to start removing the obstructions, but the army chief warned that troops should not get sucked into the political crisis and insisted on keeping the army neutral, affirming the right to demonstrate peacefully.

In unusual comments on the political situation, high-ranking army officials also highlighted that the ongoing and deepening economic crisis was having effects on morale among the security forces. Discontent is brewing in the ranks, as the financial crisis is wiping out most of the value of their salaries and unrest and crime are surging. “Soldiers are going hungry like the people,” an army chief said on Monday.

In response, the Lebanese parliament is set to meet in a legislative session Friday to endorse an urgent draft law to compensate security forces for the increased cost of living.

No political action in sight

Adding to the despair, the country is at a political deadlock and there seems to be no government plan to get out of the crisis in sight. The Diab government formally resigned after the massive Beirut port explosion last August, which killed more than 200 people, and has failed to form a new cabinet since then. A new cabinet can tackle the country’s worsening economic and social crises.

Former prime minister Saad Hariri was nominated as successor, but has yet to form a government because political parties are quarreling over cabinet positions. Disagreements are deeply entrenched between Mr Hariri’s party, the Future Movement, and President Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement. Hariri announced that he has presented Aoun with a “cabinet consisting of 18 ministers who are non-partisan specialists”, but Aoun objected to the cabinet, because they had been “especially Christians” and they had been named “without the agreement of the presidency.”

In most recent developments, the Lebanese president’s son-in-law and de facto president Gebran Bassil gave a speech in late February, in which he made little effort to facilitate the task of forming a cabinet. Instead, according to analysts, he used the speech to present himself as the de facto president and to laud the efforts of Hezbollah. The Islamist political movement wishes to obtain at least a third of the ministerial portfolios, because this will allow it to control government decisions. Hariri emphasises that the cabinet should consist of non-partisan specialists in order to make much-needed reforms.

In a desperate attempt to get parties back to the negotiating table, Lebanon’s caretaker prime minister Hassan Diab threatened in a televised speech on Saturday to “withdraw” from his duties unless Lebanese politicians agree to form a new government. It is feared that his ultimatum will fall on deaf ears.

Sources:

France24, TheArabWeekly, DailyStar1, TheNationalNews1, DailyStar2, TheNationalNews2, TheNationalNews3, AlJazeera

Image: REUTERS/Mohamed Azakir