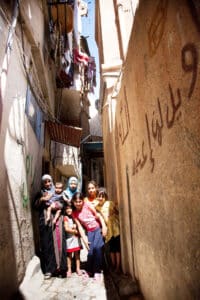

Beirut 2019: Flickr

Hundreds of retired army and police veterans, joined by angry depositors and other protestors, clashed with security forces in Beirut as they demonstrated against low pensions and deteriorating economic conditions. Security forces fired teargas at retired soldiers after the veterans – angry at a lack of action to address the currency crisis and their devaluing pensions – repeatedly attempted to storm the government palace in the capital’s city centre.

The protests came as the local currency continues to plunge to record lows against the US dollar on the parallel market. With public sector salaries paid out in Lebanese money, some employees are paid as little as the equivalent of 50 dollars. One of the protestors is Mostafa Morian, a 64 year old veteran who served in the Lebanese army for 22 years and currently makes the equivalent of 40 US dollars per month. “They are protecting those thugs”, he said, nodding in the direction of the country’s parliament building. “Tomorrow they are going to find those same thugs standing on their necks. Their fate will be the same as ours soon though”.

Since the 2019 economic collapse is one of the worst in the modern world, according to the World Bank. Since then, more than 80 percent of the population has been pushed into poverty, with the local currency losing more then 98 percent of its value. A member of Orgero’s Union, a state-run telecoms company, said: “Our salary is worth nothing because of the currency collapse, our demands are the same as other public sector employees: we want our salaries to be tied to the dollar”. At the beginning of the crisis, Lebanon’s commercial banks imposed informal capital control laws that have meant depositors have been locked out of much of their savings, further driving down their quality of life.

Political unrest

This week there was a lot of unrest in Lebanon, because the country had two different time zones. Lebanon’s caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati decided to postpone daylight savings time by one month, which took effect on Sunday morning. The decision coincided with the start of the Ramadan, and was seen as a concession to allow those observing the holiday to break their fasts at 6pm rather than 7pm. The result was confusion, political displeasure, sectarian turbulence and logistical chaos. Government institutions and public schools kept clocks back, while churches, some private schools and a number of media outlets refused to comply which resulted in two different time zones in the country.

Lebanon has been without a president since November due to political disagreement. This post is assigned to a Maronite Christian. The time zone discrepancy has caused many to question the nature of the arbitrary decision, perceived by the Christian leadership as an exploitation of the presidential vacuum by two Muslim leaders. The time difference immediately ignited heated political and sectarian arguments in the confessional country, where positions of power are delicately shared by Lebanon’s 18 religious sects.

But in the afternoon, after a morning of turbulence, Mikati reversed his decision to keep clocks back. Following a hastily called emergency cabinet meeting, it was decided that the logistical chaos caused by living under two simultaneous timings would end on Wednesday.

No reforms

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned that Lebanon was in a very dangerous situation a year after it committed to reforms it has failed to implement and said the government must stop borrowing from the central bank. IMF mission chief Ernesto Rigo told that the authorities should accelerate the implementation of conditions set of 3$ billion bailout. “One would have expected more in terms of implementation and approval of legislation” related to reforms, he said, noting very slow progress. “Lebanon is in a very dangerous situation,” he added. Lebanon signed a staff-level agreement with the IMF nearly one year ago but has not met the conditions to secure a full programme, which is seen as crucial for its recovery from one of the world’s worst financial crises. Lebanon still has no capital control law, has not passed legislation to resolve its banking crisis and has failed to unify multiple exchange rates for the Lebanese pound, all measures the IMF has requested.

Author: Manouk Bronzwaer