The crises in Moldova are piling up: pro-Western Prime Minister Natalia Gavrilita has resigned and President Maia Sandu has accused the Kremlin during a press conference of orchestrating a pro-Russian coup. To protect Ukraine, keep the wider region politically stable, and reward Moldova for its democratization course, it is crucial that the West stands with Chisinau.

Gavrilita resigns

Friday, February 10 marked the beginning of a turbulent week for Moldova when Natalia Gavrilita – the country’s Prime Minister – suddenly announced her resignation. Gavrilita stated the ongoing crises caused by the Russian invasion in Ukraine to be the reason for her resignation. Dorin Recean – a former security advisor to Gavrilita – has been sworn in to take over her position and is expected to maintain the pro-Western course.

“I took over the government with an anti-corruption, pro-development and pro-European mandate at a time when corruption schemes had captured all the institutions and the oligarchs felt untouchable,” Gavrilita said. “We were immediately faced with energy blackmail, and those who did this hoped that we would give in.”

Ever since the start of the war in Ukraine – nearly 12 months ago – Gavrilita’s government had been plagued by multiple severe crises. Most notably, Chisinau was blackmailed by Russia – Moldova’s main gas supplier – for its pro-Western course. Being a relatively poor country with only 2.6 million inhabitants, Moldova has taken in the most Ukrainian refugees per capita. The inflation – furthermore – stands at a whopping 30%.

Ukraine intercepts Russian coup plans

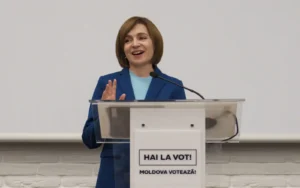

Chisinau was in the spotlight again three days later, when President Maia Sandu accused the Kremlin of plotting a coup. “The purpose of these actions is to overthrow the constitutional order, to change the legitimate power from Chisinau with an illegitimate one,” Sandu said after “quite concrete plans” were intercepted by Ukrainian security services.

Russian, Serbian, Belarusian, and Montenegrin citizens were said to enter Moldova appearing to be tourists before occupying government buildings and abducting important politicians. Serbian football fans – as well as a Montenegrin boxing team – were reportedly denied entry into Moldova over fears that they were pro-Russian saboteurs.

In response, both Serbia and Montenegro have demanded an explanation from Chisinau. Russia – moreover – has angrily denied the Moldovan claims, branding them as “absolutely unfounded and unsubstantiated”. Western allies could not confirm the existence of the coup plans, although Washington declared to be “deeply worried” by the news.

The verdicts of experts on the likelihood of the coup-accusations have varied. According to an EU-diplomat “this warning has to be taken seriously, the Russians are perfectly capable of this kind of thing. [Moldova] has weak security services, a weak military, and it’s overrun with Russian operatives, so it wouldn’t be that hard to stage violent protests there.”

Others have also emphasized the severity of the Russian threat, while being skeptical about a coup’s success probability. “Moldova is far less vulnerable than before”, according to political analyst Dionis Cenusa. He argues that Chisinau has made significant progress in becoming less dependent on Russian gas, while also successfully banning pro-Russian news outlets and improving surveillance by its secret service.

Moldova and Russia: a complicated relationship

Moldovan-Russian relations have been complicated since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Pro-Russian governments ruled in Chisinau for years, with the country heading in an increasingly pro-European and pro-Western direction since the election of Gavrilita’s government in 2021.

In 2022, Moldova was granted EU candidate status along with Ukraine. Since then, Chisinau has taken important steps in adopting obligatory EU-legislation and has received praise from the European Commission. These developments angered Moscow, which undoubtedly motivated the retaliatory steps of late.

Another source of dispute has been the region of Transnistria. Ever since a civil war in 1992, this narrow strip of land in eastern Moldova has been a pro-Russian enclave guarded by a Russian ‘peacekeeping force’, consisting of 1500 soldiers. A new anti-separatist law passed by Moldovan parliament – which technically allows Chisinau to put all of Transnistria’s separatist leaders behind bars – will make tensions increase further.

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, experts have warned that Transnistria could be used to invade Ukraine from the southwest.

The West has to stand with Moldova

Taking the aforementioned into account, three important reasons for the West to protect Moldova against the Russian threat emerge. Most urgently, a pro-Russian puppet regime in Chisinau would make southwestern Ukraine vulnerable to attack from Transnistria, as well as threaten the hard-fought political stability in the wider region.

From a moral point of view – moreover – Moldova needs to be rewarded for its important steps to EU-accession. If the West does not grant a helping hand, it would set an unpromising example to other countries trying to escape Russia’s sphere of influence.

Author: David Groenen