Last Sunday, May 15, citizens in Lebanon went to the polls for parliamentary elections. These were long-anticipated as Lebanon is hit by ‘triple crises’ – economic depression due to ineffective and corrupt governance, the coronavirus pandemic and the Beirut blast that devastated the country’s biggest port. Turnout during the elections was low – 41 percent. The main takeaway of the election is a loss for Hezbollah’s alliance – they lose their parliamentary majority. Independent candidates did well – they took thirteen seats.

Lebanon’s crises

In the 2010s, Lebanon has spiralled into a ‘deliberate economic depression’, as infamously dubbed by the World Bank. Politicians and other power-holding actors in the countries are said to be responsible for the complete impoverishment of Lebanese society. Currently, more than seventy percent of Lebanese live under the poverty line.

On top of the economic crisis, an enormous explosion devastated the Beirut port in August 2020 – this explosion has also been tied to patterns of governmental corruption in the country. In October 2019, enormous anti-government protests erupted, shaking incumbent Lebanese political leadership. Since then, many look to these elections, hoping that the incumbent Lebanese politicians may be toppled. These have been in power for decades, since a post-civil war peace deal in 1989 created an ineffective sectarian power-sharing system.

The March 8 and March 14 alliances

In this sectarian power-sharing system, two main alliances compete for power. The ‘March 8’ and ‘March 14’ alliances refer to dates during 2005 the Cedar revolution and in short were pro- and anti-Syrian blocs. ‘March 8’ consists mainly of the Maronite Christian Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), and the Shia Al-Amal and Hezbollah parties. They have had power since 2018 elections, having a 71 seat majority in the 128-seat parliament – and are blamed for the dysfunctionality of Lebanese political institutions.

Allocation of seats

Seats in the Lebanese Parliament are confessionally distributed between 11 religious sects – to accommodate all parties in the Lebanese electoral system after the 1975-1990 civil war. While confessionally distributed, MPs are elected by universal suffrage. Lebanon’s electoral system is very complicated, as it merges proportional representation with quotas to maintain the sectarian equilibrium in the country. In essence, people are elected in the seat of a certain sect per region.

It is exactly this equilibrium that has enabled the country’s elite (most of above mentioned parties) to capture Lebanon’s institutions, leading to enormous corruption and waste of public resources. Moreover, incumbent parties have redrawn electoral districts in their favour, ‘gerrymandering’, making it very difficult for new actors to enter the political arena.

Results

Final results of the May 15 polls show that ‘March 8’ lost their majority in parliament. They took 58 seats in parliament. Hezbollah and Amal together kept their 27 seats in parliament, but FPM and Hezbollah-affiliated independents did not win as much seats as in 2018. Among the high-profile losers was deputy parliament speaker Elie Ferzli, a long-time Hezbollah ally, who was ousted by a candidate backed by the Progressive Socialist Party. Hezbollah-allied Druze politician Talal Arslan also conceded his seat in parliament.

FPM has been overtaken by Lebanese Forces as the largest Christian party and overall bloc in parliament with 21 seats. Its leader Samir Geagea is a former warlord, heavily opposes Hezbollah and is affiliated with Saudi Arabia.

The main surprise at the polls were the achievements of independent opposition candidates, related to the 2019 protest movement. These went into the elections fragmented and were intimidated by incumbent political parties. Moreover, the current set-up of Lebanon’s election districts causes many difficulties for newcomer parties against existing political parties, that have entrenched political power. Together opposition took thirteen seats – a big win, taking a way of many household names in the Lebanese Parliament.

Sunni candidates related to Saad al-Hariri, the leader of the Future Movement, took seven seat. Al-Hariri boycotted the elections and called upon his followers not to vote or register as candidate.

See the provisional results below:

Lebanese Forces + allies | 21 |

Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) + allies | 9 |

Kataeb + ally | 6 |

Independence Movement | 5 |

Moawad | 2 |

Ex-Future Movement | 7 |

Jama’a Islamiya | 4 |

Rifi | 2 |

Free Patriotic Movement + allies | 20 |

Hezbollah + allies | 17 |

Amal | 15 |

Marada | 3 |

Achbach | 1 |

Nasserists + allies | 3 |

New Opposition Candidates | 13 |

|

|

|

|

TOTAL | 128 |

Expectations

The first battle in the new parliament will be on who will become its new speaker. Currently, this is Nabih Berri (Amal), in office since 1992. However, now ‘March 8’ has lost significantly, his position has come under pressure too. In the fall of this year, a new President must be elected. According to the country’s political sectarian distribution, this must be a Maronite Christian – currently Michel Aoun (FPM).

It will be very difficult to gain a majority in the current Lebanese parliament, as Lebanese Forces and ‘March 8’ are completely opposed. In order to prevent a complete paralysation of Lebanese political rule, it will be key that these parties find some sort of ‘modus vivendi’ on passing legislature. This is crucial as Lebanon has reached a staff-level agreement with the IMF on much-needed financial reform in the country.

Potential parliamentary blocs are the traditional ‘March 8’: FPM, Hezbollah, Amal and allies are now provisionally on 58 seats. ‘March 14’ – Lebanese Forces, Progressive Socialist Party, former Future Movement, Jama’a Islamiya and Rifi are on 43 seats. The stance of the new oppositional figures could thus become decisive to find majorities in parliament. Bottomline – the Lebanese parliament is perhaps even more polarized than after 2018 elections.

Election monitoring

The Lebanese Association for Democratic Elections (LADE) deployed various independent observers across the country. It documented more than 3,500 violations – mostly vote rigging, vote buying and voter intimidation. Its monitors were threatened by members of Amal, Hezbollah and Lebanese Forces.

EU election monitors were equally worried, saying that the elections were “overshadowed by widespread practices of vote buying and clientelism, which distorted the level playing field and seriously affected the voters’ choice.” Lebanon’s Interior Minister Bassam Mawlawi dismissed the allegations as minimal.

Sources: ABC News AP News I AP News II France24

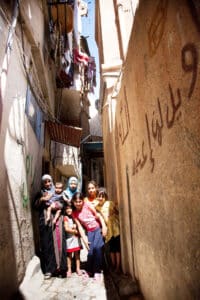

Photo: WikiMedia Commons