The newly elected Iraqi parliament has convened for the second time since the general elections on May 12 and has chosen a Speaker of Parliament, Mohammed al-Halbousi from the National Movement for Development and Reform (Al-Hal). Two deputies have also been chosen: the first is Hassan al-Kaabi from the Shia Saeroon list, and the second is Bashir Haddad of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). These elections form an important step towards the total formation of a government and cabinet; together with the preceding ratification of the election results, they jumpstarted a 90-day government formation process embedded in Iraqi law. Part of this is the rule that the country’s Prime Minister has to be a Shia Muslim, the Speaker of Parliament must be a Sunni Muslim, and the President should be a Kurd.

A recount process delayed the announcement and ratification of the definitive election results until August 19. The recount was ordered by Parliament in early June after a government report was issued, which claimed that the electronic voting system had made it possible for voting to be rigged. It added that only ballots that were deemed problematic would be recounted, which would together add up to 5 percent of the votes. The outcome, however, did not change much after the recount.

The European External Action Service (EEAS) named the election of Halbousi “the first, crucial step towards the formation of a new government in Iraq following the elections,” and urged that “the new executive […] address the multiple challenges that Iraq faces, and respond to the legitimate needs and aspirations of the Iraqi population.”

Advancement of the government formation since the May 12 elections

The government has to be formed with a win for Muqtada al-Sadr’s Saeroon list. The table below shows the election results for the political parties that gained 5 seats or more:

|

Political party and important figures |

Amount of seats in parliament |

|

Saeroon (led by Muqtada al-Sadr) |

54 |

|

Al-Fatih (led by Hadi al-Amiri) |

47 |

|

Victory Alliance/Dawa (led by Haider al-Abadi) |

42 |

|

State of Law/Dawa (led by Nouri al-Maliki) |

25 |

|

Kurdistan Democratic Party |

25 |

|

National Coalition |

21 |

|

National Wisdom Movement |

19 |

|

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) |

18 |

|

Uniters for Reform |

14 |

|

National Movement for Development and Reform |

10 |

|

Movement for Change |

5 |

Source: IHEC/Wikipedia

The different parties all ran in different provinces; Abadi’s Victory Alliance was the only group that ran in all 18 of them.

The elections did not have a high turnout: only about 45 percent of Iraqis voted, against 62 percent in the 2014 elections, and they mainly did so along ethnic lines. The results caused critique on the elections’ validity, and calls for a recount or even a re-run of the elections were heard among politicians – notably among those who had lost their seats according to the election’s results. The calls were even louder after a Baghdadi ballot storage house fire in early June.

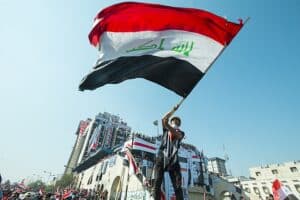

Protests and unrest

The elections caused tensions in several regions in the country. Immediately after the publication of the exit polls, conflict broke out in the Kirkuk area between supporters of the PUK on the one hand and of the rival factions like Gorran and CDJ on the other. National security forces were brought in soon to stop the conflict. However, the largest protests since the elections have taken place in the city of Basra, Iraq’s second largest city. Protests erupted there in July and intensified in early September, against the political elite, whom protesters view as corrupt and not providing government services like they should. This led to power cuts, collapsed infrastructure and a lack of safe drinking water. Further problems that protesters want the government to tackle are the funds and effort needed to rebuild the country after the IS insurgency, and the lack of available jobs.

Changing alliances

Following his win in the elections, Sadr went on to have meetings with both Al Fatih-leader Amiri, who is backed by Iran, and Victory Alliance-leader Abadi, who is in favour of the US, to discuss the options of alliances and forming a government. However, Sadr’s majority is not large enough to be able to pick a prime minster by himself, so elections in parliament have to take place for that position.

In May, it was announced that Sadr’s and Amiri’s parties had formed an alliance, in order to ease the political tensions between them and in the country in general, and in order to make the most out of their victories in terms of political influence. However, Abadi’s and Sadr’s parties announced in early September that they would form an alliance, giving them a strong enough bloc to form a government. Nevertheless, later that day Maliki’s and Amiri’s parties announced that they too had formed a bloc, which would be the largest.

The Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) has not scored particularly high in the elections in general, but has won many votes in Kirkuk, which is located in the Kurdish region. This win was disputed by other factions in the region, and they see Kirkuk as one of the regions where the votes were rigged. With its long-time leader Jalal Talabani having died last year, the PUK had presumably weakened, but the unexpected win of votes in the Kurdish region proved the support that the party still enjoys there.

Ties with Iran and the US

Another problem for the new Iraqi government to handle is balancing the interests of its two major allies, Iran and the US, in a period when there are tensions between the two over Iran’s nuclear deal and each seeks to drive the other’s influence out of Iraq. Both states have links with one or more political factions: both Amiri’s and Maliki’s groups are backed by Iran, while Abadi is favoured by the US. Sadr, on the other hand, rejects the influence of both states and advocates for totally independent politics.

Four days after the election, Iran’s Major-General Qassem Soleimani travelled to Iraq to discuss the outcome of the elections and to promote an Iran-backed national government. On the other hand, Sadr has been in touch with representatives from the US government and has more or less reassured them that he will not attack American targets, and that they are on the same page in terms of Iranian influence in the region. Even though Sadr has claimed that he rejects both Iranian and American influence in Iraq, these reassurances seem to represent his preference for relations with the latter over the former.

The fact that Abadi will most likely not win a second term as Iraq’s prime minister will have consequences for the US’s influence in the country. In the same line of thought, the possibility of an Iran-backed politician to gain the post will mean more influence for Iran in its neighbour’s political affairs. It will not be Sadr, since he did not run in the elections, but someone from his bloc is a possible option. Nor will it be Amiri, as he has withdrawn his candidacy for the post mid-September. Whichever faction will lead the government in the end, they will have to rebuild the country, restart the economy, maintain national stability among the present tensions, and deal with the interests of both Iran and the United States in the country.

Sources: Reuters, Reuters II, Reuters III, Reuters IV, EEAS, BBC, Rudaw, Al-Jazeera

Photo: Flickr