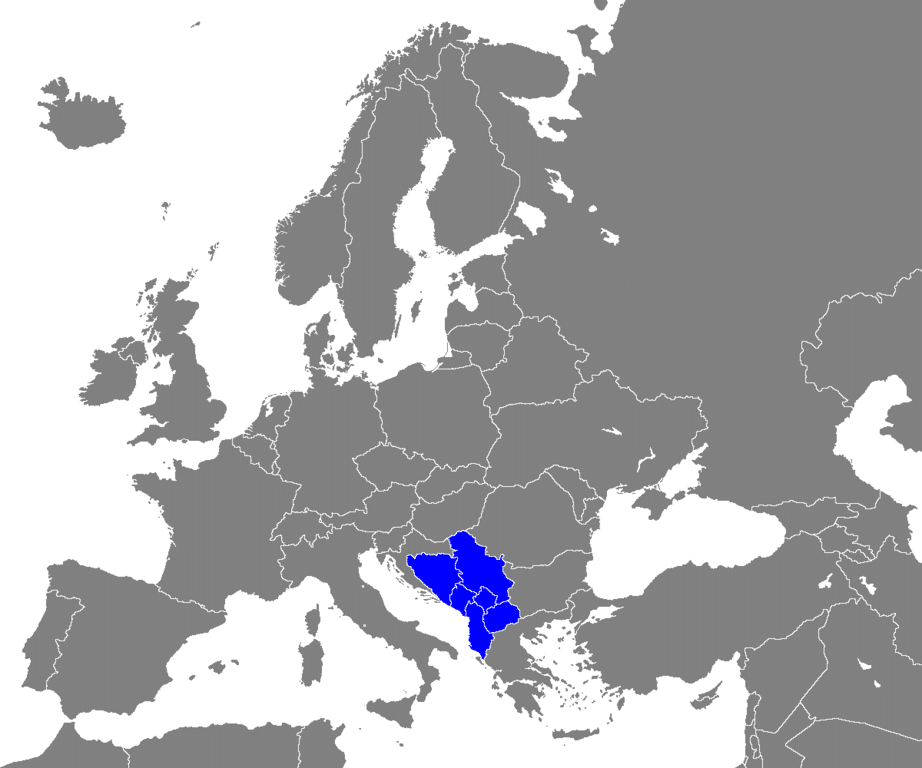

The coronavirus crisis in the Western Balkans is not coming to an end. According to official records, the numbers of daily new infections were decreasing at the end of spring, and governments started reopening and easing measures. However, the trend has been reversed, and COVID-19 is again predominant issues in the region.

Human rights violations

How the countries of the Western Balkans responded to the crisis has amplified existing cracks in the region’s unconsolidated democratic systems, along with problems related to the rule of law and democratic performance. Some measures introduced by the governments were in direct conflict with the principles of legality and human rights.

For instance, in Montenegro, the National Coordination Body for Infectious Diseases published the identities of persons ordered to undergo two weeks of self-isolation on the government’s website just days after the start of restrictive measures. In addition to violating the Constitution and the Law on Personal Data Protection, the government has enabled further misuse of personal data, as in the example of an application that, depending on location, allows you to identify persons in self-isolation in your vicinity.

At the beginning of the crisis, all countriesin the region closed their borders. However, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canton 10 (Hercegbosanska County) banned its citizens from entering its territory. The decision was swiftly withdrawn after harsh reactions.

In Serbia, people took to the streets to protest against the return of the curfew in the capital Belgrade. The government had imposed the strictest lockdown measures in the region in the earlier stages of the outbreak but rashly lifted restrictions ahead of parliamentary elections on the 21st of June. Therefore protests were initially triggered by Aleksandar Vucic’s plans to reintroduce lockdown measures but fastly grew into an expression of dissatisfaction with the overall work of the government, corruption, manipulation of COVID-19 data and death causes by corona. During the first two days, protests were extremely violent, with numerous clashes between police and protesters. Videos that went viral on the social media show police officers hitting people sitting peacefully on a park bench, police beating and stepping on the head of a man lying on the floor and many other disturbing scenes.

Personalisation of power

Moreover, in countries like Serbia and Albania, there is an increasing personalisation of power, with President Aleksandar Vucic and Prime Minister Edi Rama playing the leading role in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic and being omnipresent. Parliaments were dissolved, and checks and balances are often ignored in the name of executive power. Additionally, Vucic declared a state of emergency in Serbia. That was illegitimate from a constitutional and legal perspective since the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia places the introduction of a state of emergency under the jurisdiction of the Parliament. During state of emergency in Serbia, the most alarming issue concerning the functioning of the judiciary in Serbia was so called “Skype decree”. Namely this measure allows criminal proceedings before a court to be held via video conference call, which is in violation of international human rights standards as well as the Constitution of Serbia. In such proceedings the accused lacks proximity to lawyers or could have bad internt connection which is enough to lead to breaches of the right to fair trial.

Media: fake news and panic

The media sector in the region is already weakened due to constant pressure from governments and declining democracy. The lack of reliable and accurate information, coupled with irresponsible statements by government officials, led to collective stress and destroyed trust in the state. For instance, the government-controlled media in Serbia, such as the Kurir and Informer newspapers, were sowing panic and the spread of fake news was so prevalent in Bosnia and Herzegovina that the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media had to express his concern in an official statement. Governments have also abused their extraordinary powers to hinder the work of independent media, as demonstrated by the arrest of journalist Ana Lalic for a critical article about how equipped the hospital in Vojvodina was. Although she was soon released from custody, this case highlights the dangers of the state’s reactions to independent and critical journalism.

Elections and overthrow of the government at the midst of a pandemic

Coronavirus outbreak also affected elections in the region. In Serbia, the original election date was the 26th of April but had to be postponed to the 21st of June due to COVID-19. While all parties were forced to stop their campaigns when the country went into lockdown, Vucic used the media outlets to continue to promote his party and ridicule the opposition covertly. Just prior elections, the government announced a new cycle of assistance to mitigate the harmful effects of the coronavirus pandemic. One of the measures included handing out 100 euros to everyone over 18, which is seen as pre-election bribing. A similar strategy was used in North Macedonia. The government gave the payment cards loaded with 9,000 denars in credit to the citizens in households earning less than 15,000 dinars ($273) a month. They had to spend it on on locally made products and local services within 30 days. In both Serbia and North Macedonia, the incumbent parties won the elections.

Despite the fact that the conflict between former Prime Minister Kurti and President Thaci has been going on for some time, the debate on the state of emergency that could strengthen the weakened figure of the president, has caused a political crisis in Kosovo. Kosovo is the first case of a vote of no confidence and the overthrow of the government during the coronavirus pandemic. Subsequently, Thaci appointed Avdullah Hoti as Prime Minister Designate and on the 3rd of June, the parliament voted the new government with 61 votes in favour.

The COVID-19 crisis further exposed systemic weaknesses and problems in the Western Balkans. Thus upcoming assessments of EU-related reforms by the European Commission and member states need to take the impact of the coronavirus crisis into consideration, without compromising on key principles of rule of law and democracy.

Sources: European Western Balkans, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Radio Free Europe, N1

Photo: Wikipedia