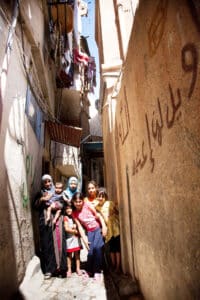

Anti-gov’t protests in Beirut, Lebanon in 2019 (photo: WikiMedia Commons)

On this Sunday, May 15, Lebanon will see the long-expected parliamentary elections in the country. In the 2010s, Lebanon has spiralled into a ‘deliberate economic depression’, as infamously dubbed by the World Bank. Politicians and other power-holding actors in the countries are said to be responsible for the complete impoverishment of Lebanese society. Currently, more than seventy percent of Lebanese live under the poverty line.

On top of the economic crisis, an enormous explosion devastated the Beirut port in August 2020 – this explosion has also been tied to patterns of governmental corruption in the country. In October 2019, enormous anti-government protests erupted, shaking incumbent Lebanese political leadership. Since then, many look to these elections, hoping that the incumbent Lebanese politicians may be toppled. These have been in power for decades, since a post-civil war peace deal in 1989 created an ineffective sectarian power-sharing system.

Who are running?

A poll by the German Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS) has shown that major changes could take place during these elections as 44.8% of Lebanese intend not to vote for the same party as in last elections in 2018. This could be a major shift, as Lebanese elections have, while anticipated, often not produced a shock at the polls. See the KAS poll below.

Date | Sample size | Amal | FPM | Future | Hezbollah | Inde-pendent | LF | Kataeb | PSP | SSNP | Other |

10-15 December 2021 (KAS poll) | 1,200 | 3% | 6.8% | 6.2% | 14.7% | 25.7% | 11.5% | 4.2% | 2.2% | 1.2% | 24.5% |

2018 general election | All voters | 9.41% | 8.15% | 10.22% | 16.44% | 5.34% | 7.32% | 1.82% | 4.60% | 1.33% | Rest |

Independent candidates are polling high in this KAS poll. Many of these are affiliated with the 2019 protest movement and hope to do well and profit from the anger of the Lebanese towards incumbent political parties.

Hezbollah is polling second-best. The Shia-affiliated party is extremely powerful, especially in Lebanon’s south, where it has a loyal voter base. Hassan Nasrallah is Hezbollah’s leader since 1992. The party profits from clientelism and patronage networks. Next to its political wing, it has an armed faction that repeatedly clashes with protesters, security forces and other political parties in Lebanon. The party is affiliated to Iran and is designated as a terrorist organization by several countries and the EU.

The Amal Movement, led by Nabih Berri, is also a Shia-affiliated party. They are tied to Hezbollah and also have an armed wing that can be traced back to the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990). Amal also has very loyal constituencies in predominant Shia areas. They clash often with Lebanese security forces and protest movements. Two former ministers, Ali Hassan Khalil and Ghazi Zeaiter, are running for the Amal party, while wanted for questioning regarding the Beirut blast.

The Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), led by Gebran Bassil, is Lebanon’s Maronite Christian party. FPM co-operates with Hezbollah and Amal in Lebanon’s political horse-trading scheme in which Michel Aoun, Lebanon’s President and well-known FPM figure, has been elected President of Lebanon in recent years. Just like Amal and Hezbollah leaders, FPM’s leader Bassil was sanctioned by the US due to ‘systematic corruption’.

The Future Movement is a Sunni-affiliated party in Lebanon that is opposed to Hezbollah and characterized by its leaders Rafik and Saad al-Hariri. Rafik Hariri was assassinated in 2005 (a Netherlands-based court linked the murder to members of Hezbollah). He was a major figure in Lebanese post-civil war politics. His son Saad has been Prime Minister in the period before the 2019 anti-governmental protest, after which he stepped down. He came back as PM after the 2020 Beirut Blast, and stepped down for the second time, unable to form a government.

In February 2022, Saad al-Hariri said he would boycott the May elections, an unexpected decision to many observers. He cited “Iranian influence, our indecisiveness with the international community, internal divisions and sectarian divisions” for his decision to boycott the elections. The Future Movement will not run candidates in elections, and only independent Sunni candidates of the party will be present.

The Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) is a social democratic led by Walid Jumblatt. Its confessional base is the Druze sect. They have a long history in Lebanese politics and oppose the Hezbollah-Amal-FPM co-operation framework.

The Lebanese Forces and Kataeb are Christian-affiliated parties with large clientelist networks, both heavily dependent upon Christian constituencies and former civil war militias. They often clash with Hezbollah and other Shia-affiliated parties.

So, how are seats allocated?

Seats in the Lebanese Parliament are confessionally distributed between 11 religious sects – to accommodate all parties in the Lebanese electoral system after the 1975-1990 civil war. While confessionally distributed, MPs are elected by universal suffrage. Lebanon’s electoral system is very complicated, as it merges proportional representation with quotas to maintain the sectarian equilibrium in the country.

It is exactly this equilibrium that has enabled the country’s elite (most of above mentioned parties) to capture Lebanon’s institutions, leading to enormous corruption and waste of public resources. Moreover, incumbent parties have redrawn electoral districts in their favour, ‘gerrymandering’, making it very difficult for new actors to enter the political arena.

Moreover, the president must always be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni and the speaker of parliament a Shia. All powerful positions in Lebanon can be traced back to a sectarian powerplay, leading to a peculiar system in which all parties are trying to hold on to their ‘pillar’ of power. Currently, a coalition of national unity, led by Prime Minister Najib Mikati (Azm movement) governs Lebanon. Mikati will not run-in upcoming elections. He is a Sunni Muslim, just like Saad al-Hariri, meaning that a seat vacuum looms in Sunni-allocated seats. Therefore, many new candidates have the opportunity to be elected in these seats.

On the outlook for…

The leftist platform Citizens in a State (MMFD) is a party to look out for. They have listed 52 independent candidates across Lebanon and were a party to the 2019 October revolution. Alongside other independents, this civic platform could be a surprise at the polls as many disillusioned Lebanese may want to vote for a new party in the polls.

In the northern city of Jounieh, well-known former Al-Gadeed journalist Jad Ghosn runs for MMFD. He earlier said: “I would feel like a hypocrite if I opposed the current political parties with all I have without actually fighting them from the inside.”

Many are also anticipating a success for parties such as Khat Ahmar (Red Line), Li Haki (My Right) and the People’s Anti-Corruption Observatory, with prominent civil society actors, such as former Bar Association head Melhem Khalaf, activist Yahya Mawlood, and the lawyers Ali Abbas, Ayman Raad and Wassef Haraka. Their chances of winning seats have increased now Mikati and al-Hariri have decided not to join the elections.

103 lists are registered, with 1,043 candidates, of which 155 women. Many young candidates and independents run in comparison to the 2018 elections.

Expatriates

On May 9, more than 100,000 Lebanese citizens living abroad cast their votes for the parliamentary elections. Overall turnout among the Lebanese diaspora voting was around sixty percent – this is three times higher than during 2018 elections. This might be a positive sign towards a high turnout next Sunday. It is expected that the large numbers of Lebanese expatriates will vote for activist and independent candidates.

There are many concerns regarding early voting by Lebanese expatriates. In 2018, 479 overseas polling stations were declared ‘invalid’, without any further explanation given by officials.

International institutions and election monitoring

International actors will closely watch the Lebanese elections. Earlier this year, Lebanon reached a staff-level agreement with the IMF regarding a large investment program, tied to major economic reforms. This are expected to further impoverish Lebanon, as it is accompanied with an extensive austerity program.

The US and EU have long pushed for the elections to be held in time, as they see it as a crucial feat of regaining trust and legitimacy for Lebanese politics. However, by pushing for the original date, the Lebanese Supervisory Commission for Elections seem woefully underprepared as they are heavily underfunded. The US and EU have rejected to invest in the Commission, while the Lebanese political establishment has cut the Commission’s budget from $54 million in 2018 to $18 million in 2022.

Bottomline

It is crucial for the Lebanese vote to be free and fair – however in current circumstances this is expected to be problematic. Incumbent political parties have a tight grip on their constituencies and election monitoring is of insufficient quality. As a result, it will be very challenging for new, activist parties to enter the political arena a major seat win. If this post-uprising election leads to marginal changes – as expected – it will see a new political horse-trading between the powerful, oligarchic, parties that have devastated the country for decades. If so, Lebanon is forecasted for a new period of instability, protesting and socio-economic deprivation of the country’s impoverished lower- and middle-class.

Sources: L’Orient du Jour Al Arabiya Reuters Arab News Al-Monitor Carnegie

Photo: WikiMedia Commons