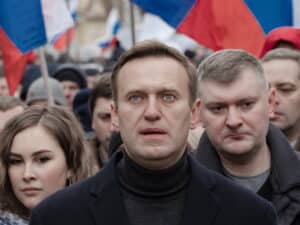

Last week Russia’s biggest opposition leader Alexei Navalny was officially refused registration by the Central Election Commission (CEC) as presidential candidate in the upcoming March 18 elections. He has appealed the Supreme Court’s ruling which upholds the CEC’s decision. Not awaiting the results of the appeal, Navalny called on his supporters to boycott the elections and take to the streets on 28 January. In 2011-2012, he was able to mobilise unprecedented crowds at protests following the elections. Will he succeed this time?

‘’Wonderful future’’ for Russia

According to the CEC, Navalny is not allowed on the ballot due to a prior conviction for embezzlement. However, his supporters say the charges are politically motivated. According to them, his right to a fair trial has been violated, as was also concluded in European Court of Human Rights rulings. That the charges are just a façade to silence the opposition leader is also argued by former Kremlin insider Gleb Pavlovsky. ‘’For three presidential elections in a row, in the elections of 2004, 2008, and 2012, they have worked to make the campaigns a politics-free zone in which the outcome was fully predetermined. Navalny is now working hard to spoil this script,’’ Pavlovsky explains. ‘’Navalny is posing a challenge and a double question to the Kremlin: ‘What will you do with me? And what will you do with this election?’’ With his charisma and command of social media, Navalny was able to build a national network of loyal supporters, including 200,000 volunteers, who coordinate 83 regional offices across the country. Although Navalny is not registered as a presidential candidate, he plans to campaign anyway.

Navalny promises in his program a ‘’wonderful future’’ for Russia. One of the main obstacles he wants to tackle is corruption. ‘’My campaign program is based on a simple fact: Russia is a very rich country, but the main reason for our [current] poverty is corruption and terrible governmental rule for the last decades,’’ Navalny said in a six-minute YouTube announcement released on 14 December. Among other things, the politician wants to increase the minimum wage to 25,000 rubles ($426), switch the presidential system to a parliamentary system, and turn the presidential terms back to 4 years (limited to two terms).

Presidential candidates

More than 20 people have expressed their wish to run for Russia’s presidency, including journalist Yekaterina Gordon of the Party of Good Deeds, Sergei Baburin of the Russian All-People Union party, liberal Grigory Yavlinksy, and business ombudsman Boris Titov. Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky will also run, but will not be a real threat to Putin. According to critics, Zhirinovsky and his LDPR have become little more than bootlickers of the President. The question remains how much chance the opposition in Russia has. President Vladimir Putin, who recently announced that he will run for the presidency seeking a fourth term, said at his annual press conference on 14 December that Russia lacks any real opposition candidates. As for Navalny, the President referred to the situation in Ukraine. ‘’We don’t want Russia to become a version of Ukraine. We don’t want that […] I’m sure the majority of Russians don’t want that and won’t allow it.’’

Divided opposition

Apart from Navlany, two opposition candidates are worth noting: Pavel Grudinin, a businessman with strong links to the farming sector, and Ksenia Sobchak, opposition journalist and a former reality television star. Grudinin was nominated by the Russian Communist Party. During an annual gathering on 23 December, the party leadership decided in a surprise move to drop long-time leader Gennady Zyuganov. With the nomination of a younger candidate – even though he is 57 years old – the party tries to attract a wider electorate. While the Communist Party is the country’s second political party, it is still far behind Putin’s ruling United Russia party. In the parliamentary elections of 2016, the Communist Party finished second after Putin’s party, obtaining only 19 per cent of the votes.

Ksenia Sobshak was nominated by Russia’s Civil Initiative Party. The former television reality star, whose father as mayor of St. Petersburg in the 1990s was a mentor to Putin, is routinely described as a ‘’socialite’’ in Russian media. However, she has become increasingly involved in the political debate and has also been critical of the Kremlin’s policies, taking part in large-scale anti-government protests after the elections of 2011 and 2012 and controversially – in Russia at least – arguing that Crimea constitutes a legal part of Ukraine.

Sobchak’s candidacy is a source of controversy in opposition circles, with many considering her a ‘’spoiler candidate’’, whose registration on 26 December is either a Kremlin-backed operation or a useful tool for the authorities to divide the fragmented opposition even further, which indeed seems to be happening. Navalny has called her a ‘’caricature of a liberal candidate’’, though later softened his rhetoric. Sobchak has already dismissed Navalny’s calls to boycott the elections, calling it ‘’pointless.’’ In her view, change must come by democratic means. ‘’If, as a result [of my candidacy], I have an opportunity to unite forces and create a strong, just party and enter the [State] Duma with it, then I think I’ll have done something meaningful for my country,’’ she said. According to her, she has already made every effort to reach out to Navalny, and even invited him to join her campaign.

A challenge?

A victory for Putin is a foregone conclusion, as election campaigns and results are routinely manipulated by the authorities. Surveys conducted by the pollster Levada Centre indicate Putin is still quite popular: a recent poll put the President’s approval ratings at 83 per cent. If Putin, who became President for the first time in 2000, wins the presidential elections on 18 March – scheduled on the anniversary of Russia’s annexation of the Crimea, which is no coincidence, as this event boosted Putin’s popularity -, he would extend his rule to 2024.

In addition, Putin will probably face little serious challenge in the upcoming polls. The opposition is divided, with most candidates unable to mobilise or unite opposition supporters and sympathisers on their own. The most popular opposition politician and the only one with the potential to do that, Alexey Navalny, has been denied a registration as candidate. His call to boycott the elections and stage mass protests just a week before them, on 28 January, constitutes an open challenge to the Kremlin. It will be interesting to see whether he again succeeds in triggering a mass movement, as in 2011-2012. In large, this will also depend on the course of action that the Kremlin chooses in dealing with this challenge.

Sources: Radiofree Europe Radiofree Europe I Moscow Times Moscow Times I Moscow Times II Moscow Times III Radiofree Europe II Radiofree Europe III